by Ivano Cavallini PhD

Professor of Musicology. Department of Cultures and Society;

past Vice-head of PhD in European Cultural Studies -

Europäische Kulturstudien, University of Palermo

author of the fundamental book "Il direttore d'orchestra. Genesi e storia di un'arte" Marsilio editore

From the second half of the nineteenth century, when Le chef d'orchestre (1856) by Hector Berlioz appeared, the initially narrow ambit of the teaching of conducting was considerably enriched with manuals, designed to solve the technical problems connected to the execution of music that became part of the repertoire.

The formation of repertoire, let us remember, contemplates the study of scores composed between the end of the seventeenth and the entire twentieth century and is the result of a process of historicisation from which the concept of interpretation and the young discipline of conducting were born - young if compared to the most antiquated of individual instruments.

If the bibliography on conducting is a consolidated heritage in Western countries, that of Eastern European countries is almost completely unknown. Among the illustrious names of the former Soviet Union, for example, that of Ilya Musin only recently became part of the Parnassus of the great teachers of orchestral conducting thanks to the studies conducted by his spiritual heir, the maestro Ennio Nicotra.

The Musin method, revisited, enriched and disseminated by Nicotra, differs substantially from the precepts of current manuals.

The biographical notes to follow and the interview given by the Italian disciple, help to shed light on the reasons for the success achieved by the innovative practice inspired by the technique of the great Russian artist.

Ilya Alexandrovich Musin was born, according to the Julian calendar in use before the Soviet revolution, on December 24, 1903 in Kostroma.

Later, when Lenin's Russia aligned with the Gregorian one, the date was moved to January 6, 1904. And it was precisely on that day that the students traditionally gathered in the maestro's apartment to celebrate his birthday.

Later, when Lenin's Russia aligned with the Gregorian one, the date was moved to January 6, 1904. And it was precisely on that day that the students traditionally gathered in the maestro's apartment to celebrate his birthday.

Musin's father was a watchmaker and his mother died when Ilya was only six years old.

One day, around ten, playing with friends, Ilya played a simple melody on the piano, which is why his father decided to send him to study in St.Petersburg with his younger sister.

Thus, still a child, he came to the city where he would witness events that would change the course of history and of which he always kept a vivid memory. [caption id="attachment_1669" align="alignleft" width="300"] Postponed to August 17-21[/caption] Ilya Musin devoted himself passionately to the study of the piano, until on a winter's day, while practicing in an unheated room, a tendon problem occurred which forced him to abandon the instrument.

For this reason he opted for conducting under the guidance of Nikolaj Mal’ko (1883-1961), a famous conductor in the St.Petersburg conservatory.

In short, Ilya became his favorite assistant, and when Mal'ko went on tour abroad, he replaced him as a teacher. In 1929, informed of the fact that the conservatory would no longer allow him to perform outside the USSR, Mal'ko preferred not to return home and took up residence in Copenhagen.

After the drastic choice, in addition to the intense concert activity, he devoted himself to the drafting of the treatise The Conductor and his Baton (Copenhagen 1950), thanks to which he is still remembered today.

From that moment until his death, Musin was appointed to lead the conducting class for a total of seventy years of activity, to which should be added, the two assistantships. An unparalleled record.

In a short time Musin's lessons took a different path than the one drawn by Mal'ko. First of all, he imposed the stable presence of two accompanying pianists, while before the students alternated with the keyboard. Then, the didactic experience forced him to reflect at length on the most elementary questions of the discipline. For example, to explain how an attack is given, how to highlight the various nuances of accents, how to deal with the staccato and the legato, how to construct a passage following a logical thread and how to go from one tempo to another.

Moved by a great passion for teaching and to answer students' questions, he devoted himself to examining the problems that Mal'ko had never faced: the purely technical aspect connected to the communication and the transmission of an interpretative thought.

Some conductors, Bernstein and Muti just to mention, have had the rare gift of possessing an innate technique, and this also applies to Musin. He began to analyse with meticulous precision all that he did with his arms and hands as he conducted, and from this meticulous study he drew the general rules to be transmitted to the students.

Postponed to August 17-21[/caption] It enriched the subject by introducing terms of new coinage, suitable for indicating both basic gestures and particular gestures, until gradually forming an autonomous lexicon. He demonstrated the convenience of using certain gestures rather than others, through the verification of the resulting sound by the students, who were forced to rigorously monitor their capabilities. Together with the examination of the gesture of many foreign colleagues, in particular Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer, Oskar Fried, Felix Weingartner, Hans Knappertsbusch, Hermann Scherchen, Hermann Abendroth, Fritz Busch, Erich Kleiber, Fritz Stiedry, Dimitri Mitropoulos guests of the USSR until 1936, the year of border closure, all contributed to the establishment of a system of conducting that has no equal.

Several times Musin said how useful it was to look at German conductors in action. And the video recordings of their concerts attest to a common thread that links Musin's technique to the German school, even though defining the school's concept of Dirigieren raises many and justified perplexities.

Another aspect of Musin's career deserves the utmost attention. As paradoxical as it may appear, in the face of an art that does not admit fixed rules, if not the fundamental ones, the development of a 'scientific praxis' in the study of orchestral conducting was made possible thanks to the closure of an entrenched country within its own borders before and after the iron curtain.

As had happened up to a certain period with the acting of Stanislavsky, or to Haydn who threw out the premise of Viennese classicism in the lost Eisenstadt campaign, Musin succeeded in elaborating his method by virtue of an almost total isolation, favourable to creation free from external influences.

However, the long political closure of the USSR has concealed Musin's work from the viewpoint of the Western public, if we exclude countries that were part of the communist orbit admitted to entertain cultural exchanges with the former superpower.

Only since the seventies of the last century did his name begin to circulate quietly even in the West, thanks to a small number of students who were allowed to perform anywhere.

Without fuss or pay for his teaching, Musin treasured what he could learn from his most famous colleagues. In the war years, during the evacuation of the conservatory in Tashkent, the drafting of a treatise on conducting technique began, Technika dirizhirovanja, which saw the light in 1967.

Also a text written on sheets of paper that his little son Edik recovered, by searching among the garbage from the capital of Uzbekistan.

In almost three quarters of a century, hundreds of conductors have been trained at the Musin school, some of which belong to the elite of the world concert circuit: Semyon Bychkov, Yuri Temirkanov, Valery Gergiev, Rudolf Barshaj.

Ennio Nicotra was born in Palermo in 1963. After completing his studies at the conservatory of his native city, in 1989 he moved to St.Petersburg where he won a four-year scholarship to be admitted to attend the class of Ilya Musin in the “Nikolaj Rimsky-Korsakov " Academy of music.

Ennio Nicotra was born in Palermo in 1963. After completing his studies at the conservatory of his native city, in 1989 he moved to St.Petersburg where he won a four-year scholarship to be admitted to attend the class of Ilya Musin in the “Nikolaj Rimsky-Korsakov " Academy of music.

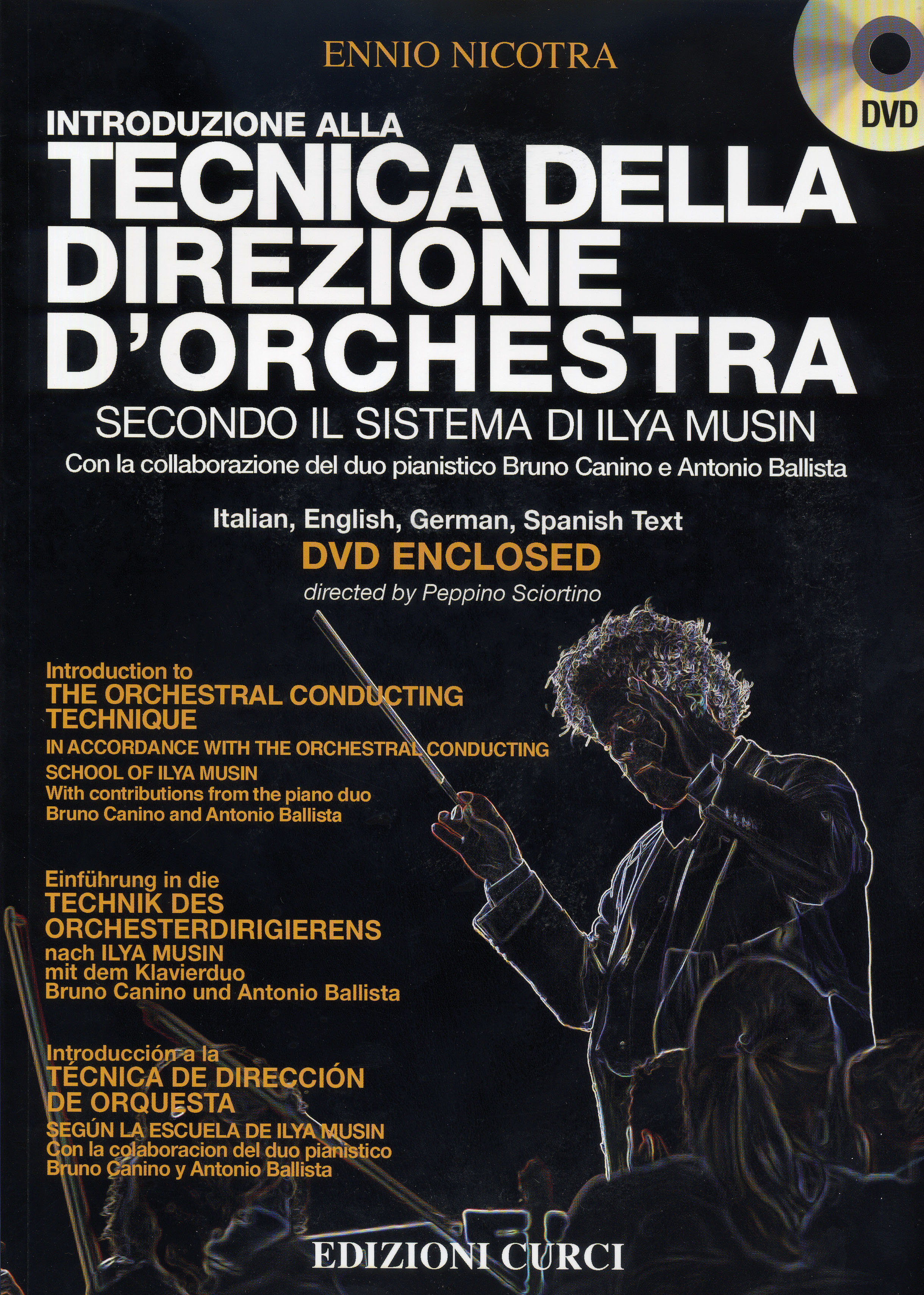

Later he was appointed Musin's assistant at the Accademia Chigiana courses. He began his career as a conductor, but devoted himself almost immediately to teaching. In 2007 he published for Edizioni Curci, a manual in four languages on the Musin method, entitled Introduction to the technique of conducting.

It is an essay that uses modern technology thanks to an accompanying DVD, with the examples made by the famous Canino - Ballista piano duo, who for the occasion were the "orchestra substitutes".

In 2002 he founded the Ilya Musin Society, into which students come from all over the world.

He holds masterclasses and annual courses in the USA, Brazil, Lebanon, Russia, France, Great Britain, Italy. Many of his students are already permanent conductors of prestigious orchestras and tread the most important stages daily.

Maestro Nicotra how did the lessons take place in Musin's class?

In the Kybalion, the book of hermetic wisdom, there is a passage that reads: "When the sound of the master's footsteps is heard, the ears of those who are ready to receive the teaching are opened." This was exactly the mood of the students as soon as we perceived Musin's presence in the corridor.

The lessons were a joy, a party, we returned home with a grateful soul for the tuition we received. During the week we worked in class with the piano duo and on Saturday morning with the orchestra. Over time I realised that in reality it is much more difficult to make two pianists sound good and exactly together, than a whole orchestra. In fact, when the orchestra feels the conductor's inability or inexperience, it prefers to ignore it and proceed alone. For this reason the technique must be studied with two pianists before moving to the orchestra.

The pianists always have their eyes on you and they forgive nothing.

The relationship with the orchestra is often distorted by the goodwill of the orchestra. I am sure that without this invisible aid that is automatically activated in dangerous situations, dozens of illustrious careers would not have been realised.

How did your desire to devote yourself to teaching arise?

I believe it was an inclination that I had always carried within.

I believe it was an inclination that I had always carried within.

What probably gave me the decisive push were the years of assistantship with Musin at the Accademia Chigiana. I arrived directly from St.Petersburg, and having completed my studies with Musin I had no other terms of comparison.

Seeing students of all races, who had years of study in famous institutions and big names, watching the difficulties of many of them in front of two pianists and then the orchestra was a great shock for me, that made me understand both the universality of the language codified by Musin, and the emptiness that his scholasticism could fill.

Is there continuity between Mal'ko's and Musin's lessons?

Once I asked this question myself. Undoubtedly Musin was a pupil of Mal'ko, and this is an undeniable fact. Mal'ko's lessons took place in the following manner: first of all in the class at that time there were no accompanying pianists, who were introduced permanently by Musin. In the 1920s, conducting students alternated with the piano.

But what left me thrilled was to learn that, once a performance was completed - perhaps in harmony with the self-critique of a new course policy - everyone expressed their opinion on the colleague's performance!

But what left me thrilled was to learn that, once a performance was completed - perhaps in harmony with the self-critique of a new course policy - everyone expressed their opinion on the colleague's performance!

Therefore, according to Musin there was not with Mal’ko, that analysis work aimed at developing and strengthening the technical and communicative aspect of the student. Some time ago, assuming that there was a line of continuity between Mal'ko and Musin, I was invited to speak at a conference that was held in a conservatory of northern Italy. But in the Mal'ko handbook I didn't find anything in common with the Musin school, and so I declined the invitation.

Was it easy to master the method?

No. Very difficult. It took me about two years to begin to understand how didactics worked. At first I saw the gestures in the air and listened to Musin's corrections, but I couldn't put the two together. I thought his observations were the result of an illusion, of his self-suggestion.

Sometimes I thought he was kidding us. It is not at all easy to connect fast gestures with the sound result. You need to have a trained eye and an uncommon ability to connect the physical action with the reaction of the instruments.

Then, very slowly, the darkness began to fade away and in the distance I began to see the light. I was able to connect the two realities, I saw and I also felt the errors and I even managed to foresee the passages which Musin would have redone with the student and also with what words he would have done it.

They were moments of unspeakable satisfaction and contentment. Unfortunately then something irreparable happened.

They were moments of unspeakable satisfaction and contentment. Unfortunately then something irreparable happened.

As he grew older, Musin’s vision already in bad shape, worsened and in the final years he overlooked many details. In practice I continued to see the errors and he remained silent. It was a painful moment when his decline occurred. I was fortunate to meet him again in full strength, despite his 86 years. He continued to teach for nine more and I would place the phase of his physical decline after he reached 92.

How did you recreate the Musin method, what was your personal contribution?

The Musin method is based on very simple principles. Watching one of his or my students conduct, one notices a certain naturalness in the gesture, but it is a condition that is hard to conquer.

The conductors who are able to co-ordinate the gestures with ease, that are able to shape the sound mass as they please, easily exercise their dominion over orchestras, and even if the latter do not always realise the whole preparatory study, they intuitively feel that the it works.

I am sure that the Musin method is perfect as it is. It cannot be changed. It cannot be improved, and if some think they can actually do it, they will damage it. I simply tried to propose it differently. I try to expose the same principles to the students and make them quickly assimilable.

I am sure that the Musin method is perfect as it is. It cannot be changed. It cannot be improved, and if some think they can actually do it, they will damage it. I simply tried to propose it differently. I try to expose the same principles to the students and make them quickly assimilable.

I explain at the same time what the foundations are on which they rest. When I was studying in class with Musin he was clear in his examples. I later, alone, tried to get to the bottom of the rationale that governed his precepts.

It was a very fruitful excavation job. I found a logical explanation to all his criticisms: in short, I could bring every detail back to the general rules. He ignored this continuous discernment of mine.

Then one day, in 1991, I went to his house. He had just received the reprint of his book, the Technika dirizhirovanja, from which I was inspired for mine. He took a copy from the package, the first, he placed a dedication and gave it to me.

I’ll let you imagine my amazement and even a little annoyance at finding all the technical principles that I had managed to conquer over the years. If he had told me immediately how to solve the technical problems I would have arrived at the same results with less effort and time.

This is why I explain the subject to my students in a different way, and it is perhaps also for this reason that they learn quickly, bearing in mind that the method is that.

Has this episode been taken into account during the writing of the manual?

Undoubtedly! In hindsight, having been forced to find the roots by myself was useful to me. In my opinion, the weak sides of Musin's book are too convoluted a language, which at times makes it incomprehensible, and the lack of a visual support that was unthinkable then. For me, who studied with him, it is clear what he means, but for a person outside his technique the narration is very cryptic.

Would Maestro like to explain in detail how he prepared his method in relation to the DVD and how he proceeded to choose the

repertoire?

The initial idea was to translate the maestro's book into Italian. When I arrived at the fifth chapter, where he delves into the technical explanation of the gestures, the translation caused me enormous difficulties because of the language, as I have already said. I realised that I would end up in a dead end and set aside the project.

The initial idea was to translate the maestro's book into Italian. When I arrived at the fifth chapter, where he delves into the technical explanation of the gestures, the translation caused me enormous difficulties because of the language, as I have already said. I realised that I would end up in a dead end and set aside the project.

I took it back when the first CD-ROMs appeared on the market, and then I thought that I could give a new shape to my work. In short, I thought it appropriate to create a more agile consultation tool than the manual to make the Musin method available to a wide audience, from the amateur to the professional.

Musin has identified specific gestures that must be carried out in a particular way to guarantee success. How can you explain them on paper?

Sometimes in St. Petersburg students came who, having studied in his manual, asked to conduct for the teacher.

The results were contradictory. It was evident that reading a written text gave rise to subjective interpretations.

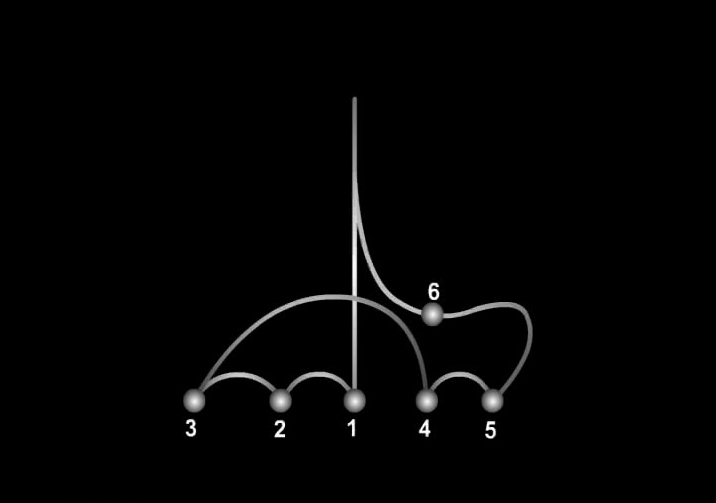

To give an example, if I limit myself to describing with a word, a gesture of a percussive nature every reader will be able to interpret it in his own way. If instead I manage to fix the interpretation with graphic and sound clarity, the reader is in the ideal place to understand the message on the fly. Since the time of Berlioz, in the treatises on conducting there are examples on the design of diachronic berries, compared to the real movement of the hands, and in comparison, with the subsequent sound translation in the realisation of the DVD.

To make the synaesthesia perfect, I included some pieces that better than others, lend themselves to the application of the notions addressed in the book. Proceeding in order, first appears the neutral layout accompanied by the graphic that the reader can follow on the video.

Below are the examples to which the scheme in question is applied. Furthermore, I left empty spaces next to the name of the scheme so that, once viewed on the DVD, the reader can write next to it in pencil, and this is a decisive step in the learning process. Reading and vision must go hand in hand, only in this way can there be a real benefit.

Below are the examples to which the scheme in question is applied. Furthermore, I left empty spaces next to the name of the scheme so that, once viewed on the DVD, the reader can write next to it in pencil, and this is a decisive step in the learning process. Reading and vision must go hand in hand, only in this way can there be a real benefit.

Reading the text without watching the video is of no use, and vice versa. Undoubtedly, technology has given me the opportunity to carry out a work of synthesis unimaginable until a few decades ago.

I was able to reduce the text to the essential and publish the volume in four languages, a process of four years. It was a nice gestation period and knowing that the Canino - Ballista duo shared the project undoubtedly was a great comfort. Of equal satisfaction is the fact that many young people have had the opportunity to come into contact with the thoughts of Musin. Just think of the many students who come with the book to my masterclasses, both in Italy and abroad. Years ago an Australian student attended one of my courses.

I was surprised by his conducting, clear, precise, unequivocal, it was inevitable to ask him if he had studied in St.Petersburg, he replied no, he had studied in my book! Nevertheless, it is not a book that shapes an orchestra conductor, it can only provide the basis for getting started. Musin identified four levels to which the student had to rise to reach a complete maturation, and Stanislavsky speaks of the same phases. My contribution stops at the first level, but it is still the key to access a larger system.